A retrospective of the artist’s work

*Portrait by Drew Friedman

12/12/2010

When Al Jaffee walks into the Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art in SoHo, the room suddenly comes alive. Admirers of the eighty-nine-year-old artist fall into orbit around him, asking for autographs. He obliges the clambering fans by handing out bookplates with his logo – a self-portrait as the “Mad Inventor” in which his hair spells out his name in cursive script. Mad magazine, once a cultural anomaly, now has an inter-generational legacy, manifested by the parents and children who surround Jaffee with equally intense ardor.

Click the image to buy the book!

The show at MoCCA wryly titled “Is this the Al Jaffee exhibit?” spans decades. It was curated by Danny Fingeroth and Arie Kaplan. The core of the exhibition is a new series of illustrations Mr. Jaffee made for his biography, Al Jaffee’s Mad Life, which was written by Mary-Lou Weisman and released in September 2010. Mr. Jaffee had come to MoCCA with a large folio of his new, autobiographical illustrations and asked, “Will you show these?” The museum was honored and overwhelmed by the prospect of a last minute show by one of comic’s elder statesman, and had scrambled to get the exhibit together quickly, so that it would be contemporaneous with the release of the book. MoCCA raised the money for matting and framing Mr. Jaffee’s illustrations on Kickstarter.com, a social networking website which allows its members to donate small sums to fund creative proposals.

The show at MoCCA wryly titled “Is this the Al Jaffee exhibit?” spans decades. It was curated by Danny Fingeroth and Arie Kaplan. The core of the exhibition is a new series of illustrations Mr. Jaffee made for his biography, Al Jaffee’s Mad Life, which was written by Mary-Lou Weisman and released in September 2010. Mr. Jaffee had come to MoCCA with a large folio of his new, autobiographical illustrations and asked, “Will you show these?” The museum was honored and overwhelmed by the prospect of a last minute show by one of comic’s elder statesman, and had scrambled to get the exhibit together quickly, so that it would be contemporaneous with the release of the book. MoCCA raised the money for matting and framing Mr. Jaffee’s illustrations on Kickstarter.com, a social networking website which allows its members to donate small sums to fund creative proposals.

The show will surprise many Mad aficionados familiar with Jaffee’s most famous visual invention, the fold-in. Viewers are used to laughing at Jaffe’s visual jokes, but are stunned at the intricacy and detail of the original paintings. When faced with the unreduced original, viewers to the museum stand mesmerized by the detail and forget to laugh at they joke. They stare dumfounded as they begin to understand the many hours of labor invested in the image–suddenly comprehending it as a work of art.

Al Jaffee’s career has spanned the entire history of comics, and his work has inspired multiple generations of illustrators. Comics luminaries such as Art Spiegelman and Robert Crumb, credited with elevating comics into the realm of art and literature, both cite Mad magazine as their initial inspiration. Spiegelman, in his recent graphic autobiography, Breakdowns, recall’s Mad’s impact in the 50’s: “I studied Mad the way some kids studied the Talmud!”

Jaffee’s start in comics, in the 1940’s, coincided with the very beginning of the medium–the golden age of comics, although Jaffee eschewed the golden age craze of the super-hero. Jaffee was drawn to humor. While working for Stan Lee at Timely Comics (which would become Marvel) in the 1940’s, Jaffee created Ziggy Pig and Silly Seal as well as Super Rabbit. These characters emulated slapstick cartoons and are not well remembered today, but nonetheless they participated in the zeitgeist of the 40’s along with Superman and Captain America by fighting Nazis. Ziggy Pig and Silly Seal didn’t have super powers, so instead they improvised ersatz weapons out of absurd materials; Ziggy Pig once carved a machine gun out of ice that shot snowballs. Super Rabbit’s arch nemesis was a pig with a Hitler mustache named “Super Nazi.” Super Rabbit’s battles against Super Nazi were pure entertainment in the spirit of the times, they didn’t reach the level of incisive cultural criticism Jaffee would later become known for at Mad.

In the 1940’s super-hero comics were a lucrative industry, but Jaffee was already a concerted humorist. Rather than create the next Superman, he lampooned the whole concept with his Inferior Man, a super-hero who’s only power was his ineptitude. Jaffee’s devotion to humor left him on the outside of the super-hero craze of the golden age of comics. While cartoonists such as Jack Kirby would become celebrated as creative artists, Jaffe ended up working the grind of Timely’s romance line. He ended up on the comic Patsy Walker, a teen romance comic along the lines of a steamier Archie, which paid well but demanded intense hours and afforded little creative freedom.

Jaffee’s turning point came when he finally quit Patsy Walker to follow Harvey Kurtzman into humor illustration. Kurtzman and Jaffee had known each other since high school–they had both been students in the first year of La Guardia’s special high school of music and art. Kurtzman had been the founding editor of Mad in 1952, but by 1956, when Jaffee was finally fed up with Patsy Walker, Kurtzman was leaving Mad. Hugh Hefner had hired Kurtzman to start a competing humor magazine called Trump. Jaffee followed Kurtzman to Trump, but the venture would prove to be short lived–Trump folded after only two issues. Kurtzman and Jaffee would move on to the artist-owned Humbug but that magazine, although critically acclaimed, folded after 11 issues as well. The entire run of Humbug was reprinted in a two-volume hardcover set by Fantagraphics in 2009.

Finally, after Humbug folded in 1958, Jaffee arrived at Mad with no other commitments, and found the stability that would allow his inventive humor to flourish. Although he had made one-shot contributions to Mad under Kurtzman’s editorship, this was the first time he could devote himself to humor features without worrying about the magazine folding. There his features included Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions, where dull inquiries were treated to multiple choice ridicule, Al Jaffee’s Mad Inventions, and of course, the fold-In.

Although Jaffee’s Mad Inventions were always satirically excessive, they were also always functional. Jaffee happens to be an excellent mechanical engineer, a skill he developed building toys from discarded materials as a child. In fact, many of Jaffee’s inventions have been manufactured. The smokeless ashtray, which uses a fan to suck in cigarette smoke, was a Mad Invention before it was a real product. So was the multi-bladed disposable razor. One of Jaffee’s wildest inventions, a Ferris wheel parking garage, first appeared in Mad in 1977. It was formally proposed as a parking solution for the city of Providence, Rhode Island, in 2008.

Jaffe is best known for the fold-in. The first fold-in appeared in the April 1964 issue of Mad, since then Jaffee’s fold-ins have appeared in over 400 issues of Mad. The fold-in is Mad’s longest running feature, and in fact it represents one of the longest running features by a single contributor in any magazine. Jaffee created the fold-in as an irreverent response to the fold-out. Glossy magazines of the sixties, such as Life, National Geographic, Sports Illustrated and Playboy all had fold-outs as special features. Jaffee’s fold-in, rather than dramatically expanding the view, mutilated the magazine, and made the image smaller.

Many of the fold-ins cross from pure humor into sharp cultural criticism along the lines of Jonathan Swift. One notable example from 1971 comments on the plight of veterans returning from Vietnam. The caption asks “What deadly mission are more and more servicemen voluntarily going on?” The image shows a group of soldiers in a firefight. When the page is folded, it becomes a hypodermic needle and the answer to the question appears: “drug trips.”

With the release of Al Jaffee’s Mad Life this past September, many long-time fans of his artwork were stunned by the heart-wrenching story of his childhood. Ms. Weisman had been a long-time friend of Mr. Jaffee’s, and the story unfolded through conversation. Jaffee described their interaction to the audience at MoCCA:

“I think she was able to bring out of me memories that I had kind of long forgotten or moved on with …my childhood in the book is not filled with joy, but it’s filled with a lot of life.”

Jaffee created an entirely new series of illustrations for the book and found his drawing style changing as he worked. As he shared with the audience:

“I somehow automatically shifted into a style that I didn’t plan on and that I never used before, and it just seemed to be self-directed. After I finished all of them I looked back and said ‘How did I get into that mood of drawing?’”

Jaffee’s artistic ability, and his humor were born of adversity; drawing was a survival skill he had learned growing up. Jaffee was born in Savannah Georgia in 1921, but when he was six years old, in 1927, his mother Mildred, unhappy with American modernity, brought him and his three brothers, Harry, David and Bernard, back to the Lithuanian shtetl of her birth –a village named Zarasai. Confronting bullies and the hardship of shtetl life, Jaffee’s humor became a sophisticated defense.

Zarasai in 1864

“Jeziarosy. Езяросы (1864)” by Konstanty Przykorski (?) – Tygodnik Ilustrowany. Nr 270, 26.11.1864. S. 440.. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons.

While Fingeroth couldn’t find a photograph of Zarasai, he did find a 1920’s photograph of a similar Lithuanian town, with a horse pulling a cart down a cobbled street. Jaffee laughs at the photograph and addresses the audience:

“This town looks luxurious by comparison. You see the horse in the middle? This town [Zarasai] had a dinosaur. I left a Savannah that had indoor plumbing and wound up facing outhouses. It was a terrible experience, but on the other hand I learned a lot there. I learned to be very self-sufficient. I learned to entertain people with my drawing, to ingratiate myself to kids who thought my drawings were absolute magic. So I thought, what the hell, I’ll go on doing this for the rest of my life. The rest of it, this tedious story, is in the book.”

During Al’s 6 years in Zarasai, his father, Morris Jaffee, desperately tried to remain connected to his family, sending money every month which his mother donated nearly entirely in missions of tzedakah, an outward show of piety which left the four Jaffee boys constantly on the brink of starvation. Three-year old Bernard contracted spinal meningitis, leaving him both deaf and mute.

Al learned Yiddish fluently and, constantly hungry, became an accomplished thief. One of his first mad inventions was a device for stealing fruit, a long branch with a hook and a basket fixed on one end. His father had taught him to draw comics from the newspapers in Savannah, and periodically he would send packages of comics from the papers to Lithuania. Al’s drawing skill evolved as he copied the comics his father sent and illustrated the stories he studied in cheder. His drawing of Moses on top of mount Sinai was the first thing that struck him as funny. He had rubbed the watercolor with candle wax to make it shiny, and his younger brother David asked: “It’s so slippery. Won’t Moses slide down the mountain?”

As Hitler ascended to power, in 1933, Al’s father Morris liquidated his assets (destroying his career in the process) and borrowed money from relatives to find Al and his brothers in Lithuania and bring them back to New York. His mother refused to return to America, and stayed behind with her youngest child, David. David Jaffee escaped to New York in 1940 at age 13 under mysterious circumstances. Although no one knows the exact details of how David was saved or by whom, it is likely that their uncle Harry financed and arranged the trip, hiring a young polish man to serve as “kidnapper” and escort for the boy, as he traveled from Zarasai to Antwerp where he boarded the ship Westerland, bound for New York by way of England.

Even in 1940, as Nazi incursion into Lithuania seemed imminent, and partisan anti-Semitic sentiment asserted itself, Mildred Jaffee clung to the shtetl. Her fate is not known, but she was most likely killed by the Einsatzgruppen or by bloodthirsty Lithuanian partisans –her neighbors–in Zarasai in 1941. By the end of the war, the Jewish population of Lithuania had been annihilated almost completely. Years later, on a Mad company trip to Eastern Europe, Jaffee had no interest in detouring slightly to see Zarasai again.

In 1935, Jaffee was one of the students selected for the first class of Fiorello LaGuardia’s School of Music and Art, a moment that changed his life. Jaffee’s classmates in the first year of LaGuardia’s progressive school would become the core of Mad Magazine: Harvey Kurtzman was already planning a humor magazine then, and Will Elder, another important Mad artist, also attended that year. In fact, Elder and Jaffee were going to the same public school when art tests were administered to find gifted students for the program. Jaffee’s drawing for the test was a picture of Zarasai’s central square. When Jaffee and Elder were sent to the principal’s office after the test, they assumed they were in serious trouble. As Jaffe told the story for the audience:

“Usually when you were sent to the principal’s office in that day, before the enlightenment, you were to be flogged or burned at the stake. You were in trouble, some kind of trouble. Drawing without a license, I guess. We sat there and Willy turned to me and said ‘ya know, I tink dey’re gonna send us to art school!’ He had this very thick Bronx accent, and I had a very thick European accent at that time, so I said, ‘Mavybe your wright!’

Jaffe renders both accents perfectly, and the audience erupts with laughter.

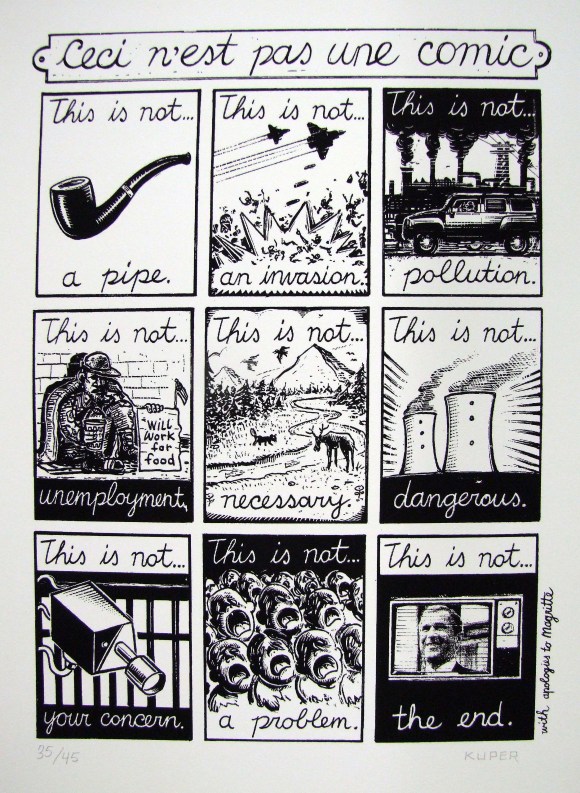

To the right of Fingeroth and Jaffee on the panel at MoCCA are the artists Tom Bunk and Peter Kuper. Throughout the presentation, Jaffee continually tries to divert attention their way, with questions like “So, what has Peter been working on lately?” but he is, inescapably, the subject of the museum’s retrospective.

Bunk is a German artist born in 1945 who worked on Garbage Pail Kids with Art Spiegelman in the 80’s and became a Mad cartoonist in the 90’s. Jaffee’s work influenced his illustration, even as he was coming of age as an artist in Hamburg.

He describes the influence of the fold-in to the audience:

“I was influenced by his sense of humor, his themes, also the way his figures moved like ballerinas. Mostly he affected my work because when my work appeared on the cover of Mad …when they folded the cover for Al’s fold-in, my artwork would be ruined as well.”

Peter Kuper, who is known for the political graphic magazine he co-founded in 1979, World War 3, as well as his comic adaptation of Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis, describes how Jaffee’s meticulous detail inspired him as a young artist:

“I remember looking at a beautifully rendered halftone comic that Al had done and there were these details on the floor –a little bone [for instance]. The idea that there were adults out there in the world spending all this extra energy in their work –the idea that you could grow up to do that, adding your own bones on the floor so to speak, was a revelation.”

One wall of drawings and paintings at the MoCCA exhibit gained a special significance in early December. Elaine Kaufman, the famous New York restaurateur, died on December 4th. Elaine’s is a writer’s hangout¬, and Kaufman was known for supporting journalists in the form of long tabs they never had to pay. Consequently, her restaurant became a meeting place for the New York intelligentsia where no one would be asked for autographs. On any given day during the 70’s at Elaine’s, one might find Norman Mailer, Woody Allen, and Abbie Hoffman in conversation. Esquire magazine hired Al Jaffee and Harvey Kurtzman to do an illustration for an article about Elaine’s. Jaffee and Kurtzman were by then longtime collaborators, and Kurtzman was notorious for his perfectionism and meticulous editing. Jaffe’s initial sketch had shown caricatures of writers crowding together in the small restaurant, talking animatedly. Kurtzman used direct visual editing–he placed a sheet of vellum over a drawing and redrew the parts he wanted changed. After Kurtzman edited the first drawing, he told Jaffee, “Make them all into penguins! They all crowd into that place like a bunch of penguins!” After many revisions, Jaffee produced penguins that looked like Abbie Hoffman, Norman Mailer, and Elaine Kaufman herself. Jaffee’s drawings and Kurtzman’s revisions had yielded an entire wall of intermediate drawings¬, but Kurtzman still wasn’t satisfied. Jaffee recalls working with the demanding Kurtzman:

“He started attaching photos of penguins to the drawings and writing notes on penguin anatomy. I felt like I was going to penguin college!”

The final painting reveals the investment of the many revisions. It is excruciatingly detailed and disarmingly funny. After the illustration was printed, Al recalls stopping in to Elaine’s and overhearing the patrons exclaim, “Someone made us all into penguins!”

A separate space at the museum is devoted entirely to the new illustrations Jaffee created for Weisman’s biography. Viewers remark on the style shift: “The drawings are much more open,” one woman says in passing. The figures are composed of clean, open lines, there are none of the convoluted details, the bones on the floor, that Jaffee is famous for. Instead of disguising a hidden image, these images reveal. One of Jaffee’s illustrations for the book was of the Zarasai town square, the real Zarasai town square, filled with cattle and children playing. This drawing, made by the 89 year old artist and published this year, must be nearly identical to Jaffee’s drawing of 1935, the drawing of Zarasai which won him a spot in the first class of La Guardia’s School of Music and Art when he was 14 years old.